And take me to the happy islands

Every time I look at the spine of this comic, I think of its hero, gargantuan, big, heavy and brutal. Polza had been good all his life until he got over it, and it was epic at once: he decided to become a homeless alcoholic, excuse me, to escape the senseless demands of society and follow only the titular blast, a moment of enlightenment , represented by the Rapa Nui monolith. Forgive the irony, but isn’t that touching? Another bored petty bourgeois who had unraveled the mysteries of life, morality, and probably a few others in one fell swoop. He undertakes a great expedition to the end of the world, and by the way, without unnecessary witnesses, he can roll around drunkenly in his own … Well, you’ll see for yourself if you read.

As you can hear, I don’t have very positive feelings about Blast’s central character . But I still believe in Larcenet, so my irony, at least until I read the second volume of this magnum opus , is directed only at the ecstatics that permeate its pages. We meet Polza when he tells his life philosophy to two police officers interrogating him as a suspect in the murder of a certain girl. Crime and Punishment? After all, radical freedom means that harming others doesn’t matter. Me and the lords of power thought the same thing – mystical nonsense. And those suggesting that there is something poetic and sexy about violence against women.

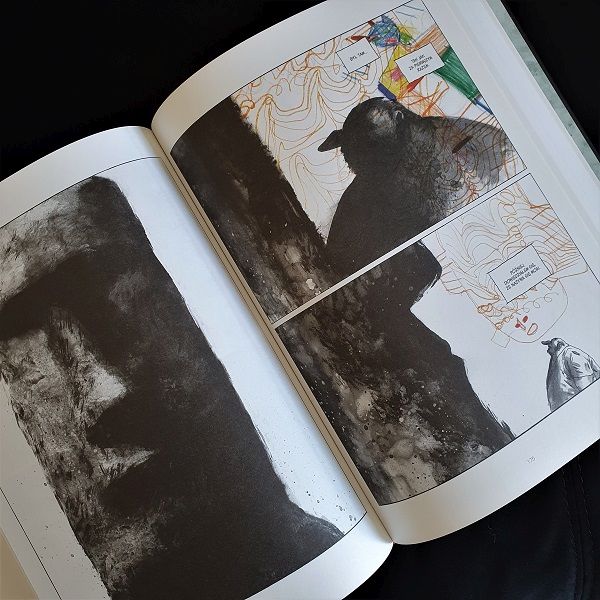

Polza annoys me like few literary characters. He demands recognition or at least sympathy, he poses as a sage, but in fact, like every addict, he only seeks quick pleasure, oblivion, escape. His ecstatic blasts , great nirvanas, are the comic’s only color pages. Larcenet smears a childish line on them, which (I hope) metaphorically expresses how great is the mystical depth of these revelations.

Whale

I’m writing this review a few months after the comic’s release, which basically worked out for me. First, some of the anger has already left me. Secondly, I can compare two works in which the big guy is a kind of metaphor for a lost life. Played by Brendan Fraser in Darren Aronofsky’s The Whale , Charlie and Polza have little in common other than size. Maybe it’s just that at some point they ask others if they think they’re disgusting – and for both of them it’s a moment of showing strength, a kind of advantage. Finally, after so many years, they have managed to come to terms with themselves and their failures, while the outsiders are still shocked by these overwhelming figures.

But what exactly disgusts the viewer looking at these two fictional characters? In the case of Charlie – ultimately nothing, even if his philosophy of honesty may seem naive to us. He’s a good man whose life is too tight. Polza, on the other hand, is terrifying because he is inhuman, and he dresses his rejection of respect for others in pseudo-intellectual justifications.

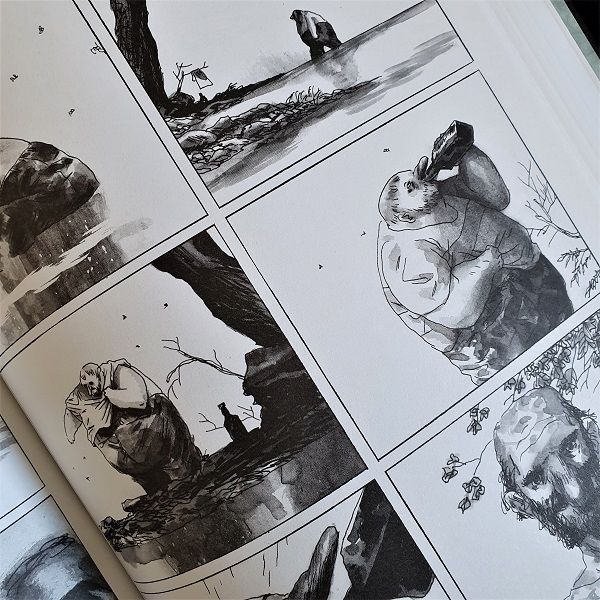

Thanks to the passage of time, I also managed to find an answer to the question of why Polza annoys me so much. Well: Larcenet’s comic is beautiful. It is full of vast, meticulously and lightly inked views, landscapes of great silence and freedom. The visual layer here seems to sublime the philosophy of the main character filled with hatred for humanity. As if she agreed with him that running away was a great beauty justifying crime. Because the one who looks at others from the position of nirvana, owes nothing to these primitive beings. It is possible that ambushes are hidden here as well: Polza’s visions were smeared with crayons by a preschooler, and the “desert areas” are full of power poles and other traces of a completely unfallen civilization. And humans, those unfortunate creatures that are constantly organizing themselves into communities,