Wydana przez Jaguara komiksowa adaptacja najsłynniejszej powieści Margaret Atwood na pewno nie jest tylko streszczeniem z obrazkami. To autorska, choć wciąż wierna oryginałowi, interpretacja, nieco inaczej rozkładająca akcenty. Rysowniczka Renée Nault każe nam zastanowić się nad estetyką przemocy i samotnością podręcznych.

The return of June

The comic book Tale of the Hand appears in Poland shortly before the premiere of the fourth season of the HBO series based on the same novel. And a few months after the black and pink protests in Poland or the USA, where women dressed in red costumes of Atwood characters appeared. It is obvious that each subsequent adaptation or reference to this exceptionally powerful dystopia provokes discussions. As I write this, the most recent conversation about Handhelds took place on the Book Market, led by Sylwia Chutnik (the recording can be found here ). Magdalena Środa, Monika Rakusa and Agnieszka Jankowiak-Maik spoke primarily about the novel, but you will also hear their enthusiastic opinions about the comic itself.

Although I read Atwood a good few years ago, my first encounter with June was in the 90s, when I was definitely too young for it. The first film adaptation of this dystopia directed by Volker Schlöndorff was shown on TVP. The impression was so strong that I was afraid of the prototype during my studies. These emotions are probably also responsible for the fact that I do not quite buy the HBO interpretation, in which the tormentor of the main character, Commander Fred, is a young man, and between him and “Freda” at some point you can feel quite (forgive the word) nice tension. And yet the main pathology of Gilead is to incapacitate half of the population, and then give the elderly young women to rape.

Susanna in an ugly world

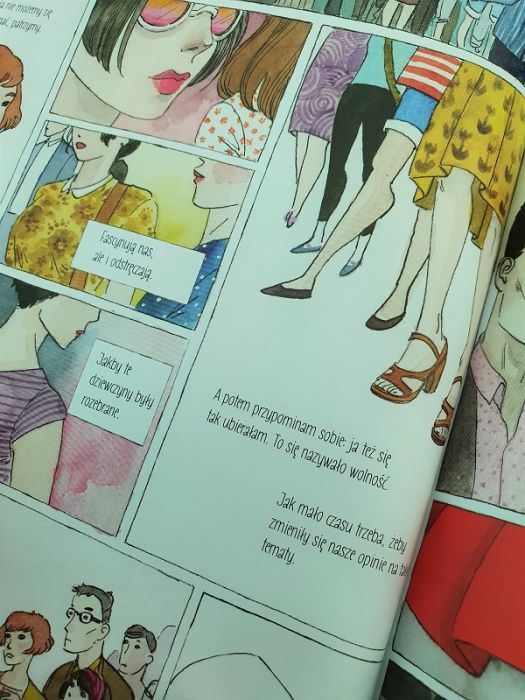

Renée Nault has a great sense of the aesthetic contrasts that are part of the criminal regime of the Handy Tale . If you browse the comic book quickly, the most interesting thing is the extremely beautiful portraits of the delicate faces of June and her friends, their slender figures in red costumes. You probably think “hola, hola, this is a dystopia, not Little Red Riding Hood . ” Wait until the first evening with the Commander. When in this tasteful, feminine world the naked butt of the lord and the ruler shines, you will immediately understand where you are.

Translating the novel into a picture brought some more interesting effects. You will see the world, paradoxically, very feminized; Since June’s incarceration in the School for Handhelds, she has contacts only with people of the same sex – Aunts, Marts (housekeepers) and Wives, or rather a specific Wife in the house where she was given “for service”. This version of life has only a few colors, because the outfits of each Gilead woman are de facto uniforms informing about her role. More colors will only appear in the memories of the heroine; after a while this everyday world will seem to you, like hers, completely unreal and strange. As if someone were sticking up pages from another comic book in which even human silhouettes were drawn completely differently.

New interpretations

The Handmaid’s Tale is an adaptation of prose, but very sparing in words. Thanks to this, June’s thoughts, or the statements of other characters, resound even stronger than in the original. It’s a bit like meditating on that very limited contact with the language that is the everyday experience of every Handmaid – after all, they aren’t actually allowed to talk to anyone.

Finally – the loneliness of the main character. The HBO version has got us used to the fact that June is constantly doing something, conspiring with someone. The plot and dialogues are dense. Meanwhile, in a comic, as in the Atwood novel, basically nothing happens, every day is repetitive boredom with no way to escape. Up and down stairs, evenings in a cell upstairs, sometimes a walk with another handbag. The narrator talks about trifles, because there is nothing else to suspend.

You will clearly see one more point here – in her usual everyday life, the main character was not an activist. She dreamed of an ordinary family life, she felt that her mother’s generation had won women’s rights permanently. Nault and Atwood do not tell the story of a struggling person, but an average girl who wanted to be able to be calm and passive. This is not an accusation but a speculation – what if this sense of security is just an illusion?

The Handmaid’s Tale in the Renée Nault adaptation is a good book in itself, so people unfamiliar with Atwood’s novel or its adaptation can easily reach for it. But also for us familiar with the quotes we include in subsequent discussions of Gilead, it is of great value. The cartoonist’s interpretation is in some respects minimalist – we get fragments from the text, and the most important threads from the plot. At the same time, it draws our attention to the difficult to accept aesthetic richness, and at the same time the (easier to accept) ugliness of the “utopia” served to American women by the Sons of Jacob. Even more than the original, he focuses his gaze on June, her painful experiences, loneliness and lack of strength. It reminds you that in its plot layer The Story it is not a story of struggle and victory – if anything, of the creators of Gilead.

May we not have to be heroes – In another conversation with Chutnik, Atwood recalled the words of a Polish resistance activist, whose memories she drew inspiration from when writing some of the threads of A Handy Tale . Nault follows this line of interpretation, completely different than in the HBO series. This contrast seems to me very important for a deeper reflection on human rights and efforts to enforce and protect them. We may not be heroines as long as no one is taking them from us. Otherwise, even this choice will be made by someone else on our behalf.