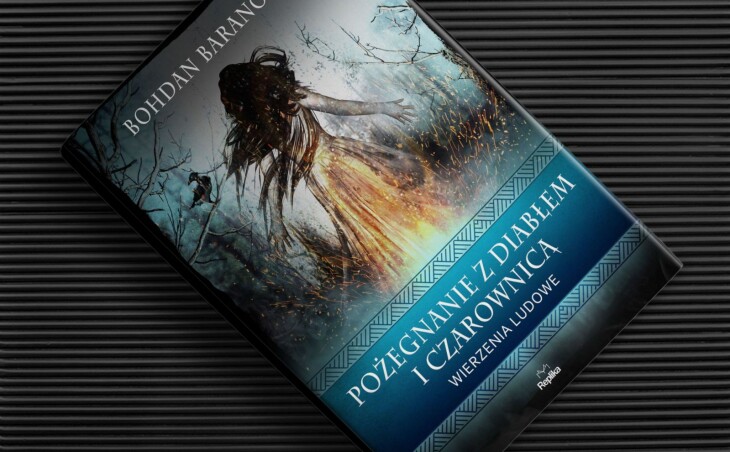

Baranowski’s book, written in the 1960s, is a compilation of rural tales and the history of witch hunts. Written in the characteristic style of that era, without hesitation calling beliefs superstitions and nonsense. Although it is old, it allows us to better understand the return of interest in Slavic traditions.

Folk beliefs

My great-grandmother was a witch. She charmed before and after the war, already “in the West”, as the family still refers to the areas in which they lived then. What was the magic about? For example, a neighbor decided that it was her grandmother’s charm that made her milk sour too quickly in her canisters. The witch had to come to the farm and undo the evil. To this end, she poured boiling water into the dishes and threw hot horseshoes into them. Magic vapors rose throughout the yard. Yes, the great-grandmother simply gripped the hygiene deficiencies. Our milk did not spoil, because the house was under the strict rule of water and soap.

Kiedy byłam malutka, na ręku zawiązywano mi czerwoną wstążkę „od złego oka”. Baranowski nie wspomina akurat o takich praktykach, ale historie takie, jak ta o mojej prababci, pojawiają się w Pożegnaniu z diabłem i czarownicą często. Niektóre mają tragiczny finał, bo jeśli wiedźma sprawiła, że ktoś zachorował, na urok „pomagało” tylko wysmarowanie ofiary krwią sprawczyni nieszczęścia. Etnograf nie ma wątpliwości, że to zabobon, ciemnota i plotka są przyczyną przemocy i samosądów, wzajemnej niechęci oraz dzielenia sąsiadów na swoich i cudzych. Nie ma też złudzeń co do ich romantyczności czy magiczności.

What’s left to the 1960s?

Baranowski conducted his own research more or less from the end of the war, almost until the 1970s. If you’ve read In the circle of ghosts and werewolves, you already know that the stories about witchcraft and magical creatures he collected did not reveal a systematic picture of folk beliefs. Folk wisdom then (probably from at least the mid-nineteenth century) had more to do with the fantasy and narrative talent of its neighbors than with any religious, Slavic or Catholic system. However, Baranowski also traces the genealogy of these stories, which undoubtedly comes down to scraps of original myths from our territory enriched with German folklore and information contained in such bestsellers as The Hammer of Witches .

The belief in witches was not initially an element of Slavic folklore. Undoubtedly, quackery traditions existed in these areas, but the evil witch is already a figure that appeared with German influence, and then with Catholic heaps. On the other hand, devils, the favorites of folk artists, are distorted figures from earlier pantheons, filtered through the church quite late, in the Middle Ages. With such a long history of forgetting and transforming, often deliberately, the elements of “primeval” folklore, adored by romantics or Young Poland, carefully preserved by poets and painters, had no less in common with the Slavic pantheon than with the fairy tales of the Grimm brothers. From our point of view, they allowed to keep undoubtedly folk traditions, but they have little in common, for example, with the archaeological discoveries on Mount Ślęża or in Biskupin.

Baranowski has a very distinctive style of writing. On the one hand, it does not leave a dry thread for those who believe in the “superstitions, nonsense and nonsense” that he has studied. As a scientist, faithful to materialism, he is also reluctant to “opium for the people”, he loudly condemns the church traditions of witch smoking and the centuries-old hatred of women or the difference they have left behind. He writes about it with a great deal of irony and humor. It was in this soil that the flower of my favorite quote from the entire book grew. Analyzing the influence of Catholicism on folk beliefs in Poland in the 16th century, he states: “finally, a certain thread has been established between Polish folk demonology and the hell of Christian science.”

Interest in witches returns

If you are interested in fantasy, including Polish fantasy, you know that the “slavtasy” trend has appeared in this field. Also beyond it, in books collecting elements of various magical systems – in Gaiman or Jadowska – there are deities and demons of Slavic origin. I will also mention native believers or extreme Turboslavians. Baranowski’s books, although they are old, allow us to look at these phenomena from a distance and reflect on how many return to the Middle Ages, and how many – to actually pre-Christian traditions. The answer is simple – the latter may in our case be only hypotheses based on archaeological analyzes. Romanticism and oral traditions tell us much younger stories. This basically applies to all of Europe. Our oldest, original religion may be Greek myths, beyond them, European legends have been so distorted that it will no longer be possible to separate the medieval elements from the older ones. We don’t even know if they are there at all.

I’ve always liked Grandma’s tales of witchcraft and ghosts. Like every child, I strongly believed in them. I also read fairy tales about rusalkas, I know the Master and Margaret by heart . All these messages contain elements of beliefs analyzed by Baranowski. We managed to reduce them to the common denominator, which is the culture of the Middle Ages, and then the Counter-Reformation. Printing and systematic growing number of parishes enabled witches to conquer the entire continent – priests read The Hammer of Witchesand then recounted its content in sermons. Whatever was before has disappeared in this first global village outburst. Maybe this is also what Baranowski teaches us – folk culture without a written tradition is just a gossip susceptible to manipulation, changing to the rhythm of bestsellers and fashions. These are beautiful, fascinating stories, but it is not worth crushing the copies for their truthfulness or originality.